Between Naming and Knowing Someone: Language, Gender, and Colonial History, by Levi C. R. Hord

Levi C. R. Hord specialises in transgender studies and queer theory. In this article, they respond to our current exhibition with Mariana Castillo Deball, looking particularly at the history and representation of We’wha (1849 – 1896), a Zuni weaver and potter featured in the show. Through We’wha’s story Hord speaks about gender, language and colonial history more broadly.

In keeping with the theme of LGBTQ+ History Month 2021, ‘Body, Mind, Spirit’, they encourage us to challenge and break free from the limited frameworks and language that we know, and to think about the inadequacy of contemporary Western ways of naming and understanding.

Words by Levi C. R. Hord

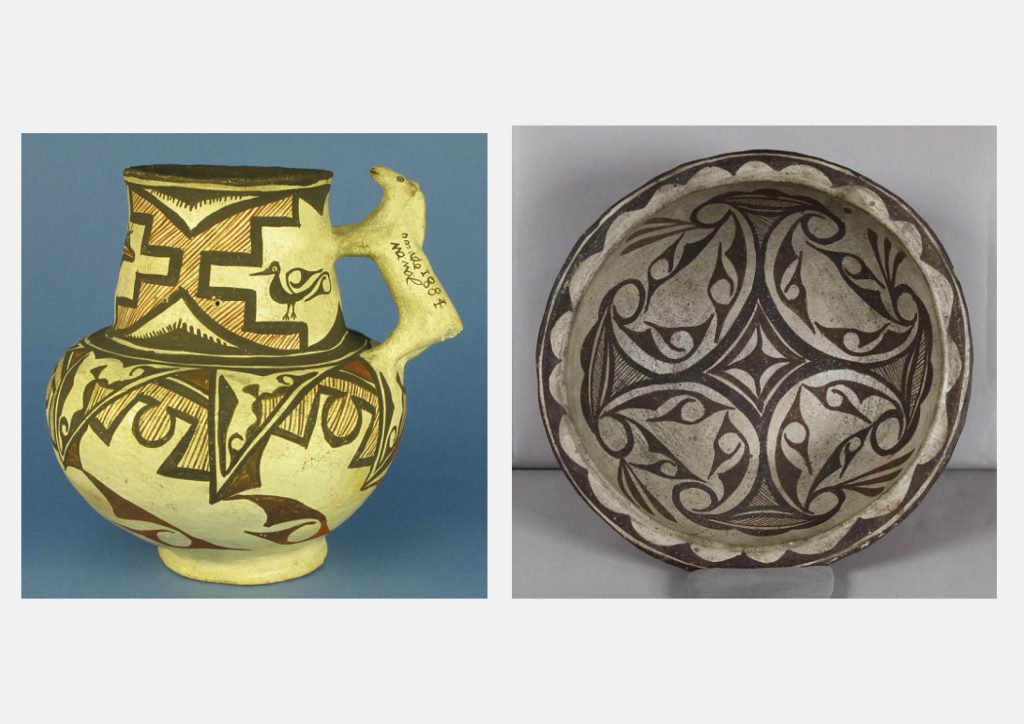

Mariana Castillo Deball’s exhibition Between making and knowing something asks us to think about the historical omissions that result from attempts to preserve anthropological “knowledge” about indigenous cultures. One of these erasures is embodied in We’wha (1849 – 1896), a gifted Zuni potter, weaver, and cultural mediator. We’wha’s admirable artistic skill had once been lost to questionable curatorial practice. But We’wha’s presence in this exhibition gives us the opportunity to think through another crucial gap in her legacy.

We’wha was neither a man nor a woman but a lhamana: someone from the Zuni Pueblos, in what is colonially known as New Mexico, who took on several social and ceremonial women’s roles, bridged and balanced differences between men and women, demonstrated considerable strength, wore a mixture of gendered clothing, and who was assigned male at birth.

I pick and choose these attributes from We’wha’s gendered history carefully: they come to me in the form of “knowledge” translated through time from early anthropologists. In the 150 years since We’wha’s life, the concept of lhamana has been altered through several lenses. We’wha has been referred to as a “berdache” (an offensive, imposed French term implying passive homosexuality), or as “gay” or “trans” (assuming a colonial affinity with European notions of gender and sexuality). We’wha has also been retrospectively reclaimed as “two-spirit,” a modern umbrella term that distinguishes specifically Native gender variance.

Gendered language has also accumulated unevenly around We’wha. Fellow Zunis are believed to have referred to her using feminine pronouns. The anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson used both “he/him” and “she/her” in writings about We’wha. Some twentieth century sources exclusively used “he/him”. Contemporary practice is to use “she/her,” recognizing We’wha’s ostensibly feminine social roles.

But at the end of the day, we do not know what language We’wha would have used to communicate her experience of gender. We’wha would never have used English gendered pronouns for herself, besides perhaps in her role as a cultural delegate. Her starting point for speaking about gender might not have included a binary at all. While we may choose the most respectful ways of referring to We’wha as a way of honoring her in our contexts, they will never be her contexts.

We’wha’s gender, and the tension around its irrepresentability in Western anthropological frameworks, underscores the power of this exhibition’s message. It emphasizes the question whether it is possible to know something deeply through the objects, stories, and terms that have been designed to display that something to an audience.

We’wha’s ceramics themselves – those which ended up in celebrated museum collections – were produced as part of a colonial exercise in knowledge consumption. Crafted in Washington D.C., their function was not practical, but representational. They were symbols meant to stand in for an entire, vibrant sociality: an inherently reductive expectation. These symbols of Zuni artistry were produced, categorized, and labelled in such a way as to make them comfortably recognizable to a non-Zuni viewer. They were never witnessed in their context, fulfilling their role, being shaped by human use.

Has the same been done to We’wha’s gender? What is the effect of our preoccupation with properly categorizing We’wha, delineating whether We’wha was cisgender or transgender, using the “correct” pronoun?

One of the principles of early anthropology was the idea that culture (particularly the cultures of the non-European “other”) could be studied according to the same scientific principles as nature – that is, objectively sorted into taxonomies. Taxonomy is the practice of categorising or grouping things or concepts into defined and discrete sets, e.g. ‘mammals’ or ‘reptiles’. When this impulse to taxonomize collides with gender variance, the result has been the brutal pathologisation of difference. In other words, difference has been viewed as something to be afraid of. Historically, the “empirical” description of indigenous gender has been part of a broader colonial violence of classification enacted on indigenous people. Taxonomy is one of the technologies through which We’wha’s gender is rendered unknowable to us in twenty-first century Oxford.

In asking ourselves how we should bring these histories out of obscurity, it is worth actively querying what we are doing when attempting to translate We’wha’s experience for broader recognition. Representation is important, as is referring to We’wha respectfully, avoiding anachronistic colonial terms. It is even more important considering that most forms of gender variance and trans experience are far from celebrated in the UK. But the impulse to classify culturally distinct modes of gender back into contemporary comfort levels is not benign.

Perhaps even more important than getting We’wha’s gender “right” is the practice of staying with the discomfort that we might experience encountering traces of We’wha in the archive that are meant to stand in for a lost whole. The moments where we stumble, puzzle over language, struggle to know how we should articulate We’wha to others, are unavoidable. They are also valuable. They are part of a legacy of irredeemable grief and loss, and they should be experienced as such alongside our attempts to add more terminology and more lines of categorical division to We’wha’s story.

The late trans activist Leslie Feinberg once said “I care which pronoun is used, but people have been respectful to me with the wrong pronoun and disrespectful with the right one. It matters whether someone is using the pronoun as a bigot, or if they are trying to demonstrate respect.” Within the context of history, the most important form of respect that we can show We’wha is an openness to being unsettled by the inadequacy of contemporary Western ways of naming and understanding. In other words, there is a broad gap between naming and knowing someone. This exhibition invites us to step into it.

About the author: Levi C. R. Hord specialises in transgender studies and queer theory, particularly in regard to contemporary identity formation and community building. Through their research they hope to make important theoretical interventions into social understandings of gender in order that subjugated and marginalised lives become more livable and political interventions more effective.

Visit Mariana Castillo Deball’s exhibition Between making and knowing something online, here.