In the museum with Marina Abramović

Go behind-the-scenes of Marina Abramović’s 2021 museum residency, inspiring her exhibition Gates and Portals at Modern Art Oxford. This post was written by Hannah Healey, PhD student and Abramović’s research assistant during the residency.

In August 2021 Marina Abramović arrived in Oxford. Invited by Modern Art Oxford and hosted by the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, she spent a month in the museum undertaking a period of research in preparation for an exhibition at Modern Art Oxford the following year.

During the residency, I worked as Marina’s assistant.

The city and the museum were quiet. Students hadn’t yet returned for the next academic year, and the flow of tourists to the city that had been halted by the pandemic had not yet picked back up.

The Pitt Rivers Museum sits behind the Museum of Natural History, and both are monuments to the Victorian impulse for categorisation. While the Museum of Natural History classifies the wonders of the natural world – fossils, skeletons and stones – the Pitt Rivers classifies the artefacts of a vast array of cultural worlds. Objects are displayed by type – vessels, instruments, weapons, amulets – in wooden cases that bring together huge numbers of objects from far afield, and just a few miles down the road.

Each morning began with Yorkshire tea, a quiet moment to discuss the plan for the day, and a walk through the galleries.

We peered into display cases, opened the many drawers each cabinet holds, examined their contents. We tried to read the handwritten notes that sat around the objects, partly obscured labels and tags inscribed by curators from the museum’s past. Marina would pick a section or theme to focus on, and sometimes we would be joined by curators or professors whose specialty was represented in the museum.

We sat with curator Julia Nicholson in front of tall cases holding objects from Siberia as she told us about shamanistic practices from the region, and the pioneering early women anthropologists that trained in Oxford.

Marina has a long engagement with Tibetan Buddhism, seeing in it a reflection of the long-durational embodied practices that have informed her performance work. And so we spent an afternoon with objects from Tibet, guided by curator and professor Clare Harris and PhD candidate Thupten Kelsang.

In the afternoon, objects for closer examination were gathered from the museum displays by curator Nicholas Crowe and brought to the study room. This backstage area of the museum, unseen by the public, is encircled by the curators’ offices and the museum library. During our month at the museum, there were few others in this part of the building.

A layer of white polystyrene protected the objects from the hard surface of the tables they were placed upon, and around the room were boxes of gloves for handling the objects. Marina chose not to use them. Instead, she hovered above the objects, observed them from a short distance, and moved through the space around them.

Working with Nicholas, I sourced texts on the objects that held Marina’s interest. Some, written by the historic collectors, gave insight into how they came to be in the museum. Others, by more contemporary academics, reflected on the loss or persistence of the objects in the cultures and communities they originate from.

I tried to find the stories of the objects.

Where they came from

who made them

how they were used

why they were important.

The lives they had before becoming museum exhibits.

An idea that recurred was gates. Transportive and transformative objects.

Among the objects gathered by Nicholas was a small animal figure from Nigeria, an Agu-‘nsi. It came to the Pitt Rivers via a British colonial district officer named Percy Talbot, who lived in Nigeria from 1902 to 1931. It is recorded as coming from the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria, from the Etcheor Igbo (also Ibo) peoples, and is said to have been used by a medicine man for divination.

Incorporated into Marina’s study process were other methods for understanding the objects. On her first day in the city, we visited the art supply shop on Broad Street and she selected sketchpads, loose sheets of paper, pastels, a few pencils.

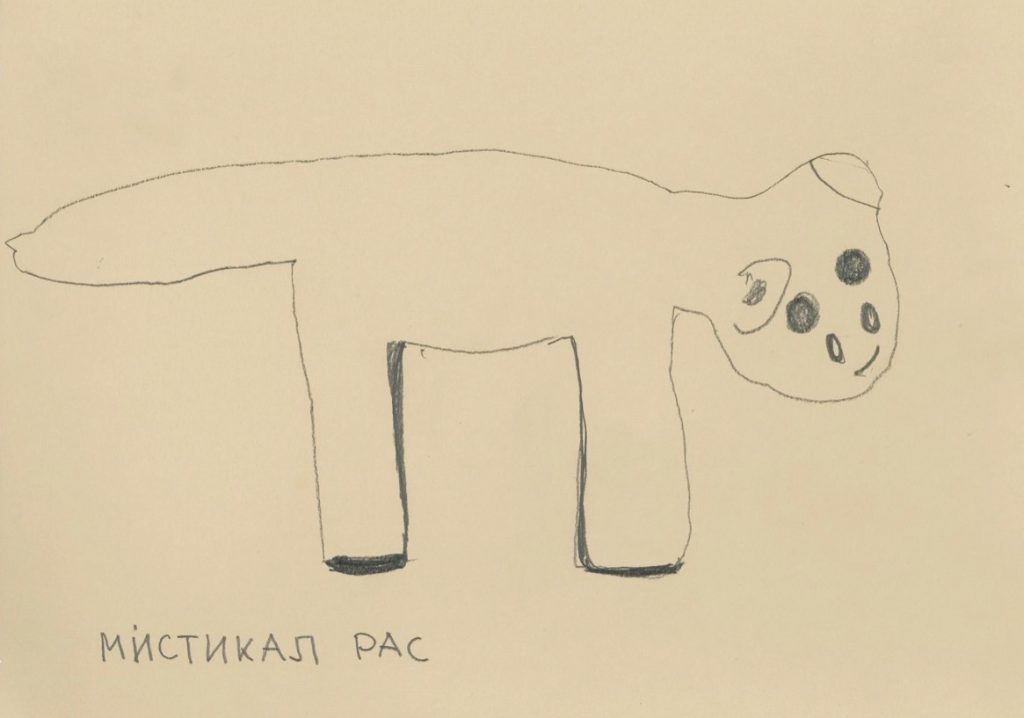

After observing and discussing the objects together, Marina would be left to draw. On pages not larger than A4, she drew the objects that interested her, often several times and from differing angles. She gave them titles, written in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Marina drew the Agu-‘nsi, the length of its body and its rounded face.

With curved ears, four legs, and a tail, the Agu-‘nsi resembles a small dog.

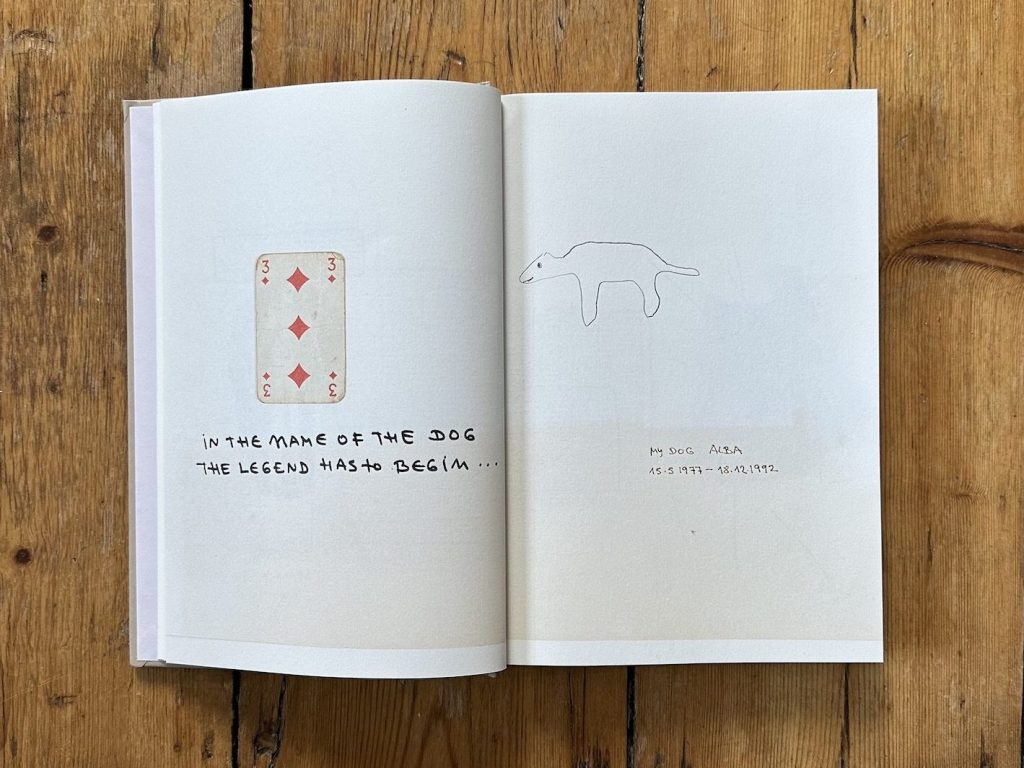

The figure reminded Marina of her own dog, called Alba, who lived with Marina and her partner and collaborator Ulay as they travelled across Europe in a van working on shared performances.

In the final week of our time at the Pitt Rivers, Marina made a new piece of work drawing on objects from the museum collections.

In the study room, Nicholas gathered thirteen objects selected from the vast number we had looked at. While the interactions were filmed, Marina held her hands over each item for several minutes. Then, each one was removed, and she held her hands once again over the space that they had just occupied. Feeling the presence and absence of the objects.

Here again the Agu-‘nsi appeared.

In the year after the residency, as plans were made for the exhibition, Marina, her studio, myself, and staff from Modern Art Oxford and the Pitt Rivers Museum worked on a publication. The small book, entitled Gates and Portals, gives an insight into the residency in the context of Marina’s lifelong curiosity and research.

Included is a series of images of objects that Marina has collected in her many travels. Brought together to form a ‘private archaeology’, she describes the objects as ‘materialised memories’.

Among them is a pair of images: a playing card, the three of diamonds, captioned ‘in the name of the dog the legend has to begin’, and on the opposite page a drawing of a dog, shaped not unlike the Agu-‘nsi, captioned ‘My dog Alba / 15.5.1977 –18.12.1992’.

An image of a dog recurring through a personal mythology.

Our time at the Pitt Rivers was a rare opportunity to spend all day, day after day, with the objects of a museum. Together, the book and film present the culmination of a month spent with the objects of the Pitt Rivers, the process of slowing down and observing.

In these interactions between the object and the artist, connections emerge between objects and the person who approaches them. Shaped by our interests and personal histories, the stories museums tell us, and the stories we tell ourselves.

Hannah Healey is an art history researcher and writer. She is currently a PhD candidate at the Courtauld Institute of Art researching Artists for Democracy, experimental art, and radical politics in 1970s London.